By: Alex Byrne – 27 November 2018

Alex Byrne sets out the ways practitioners can protect themselves from the charge of money laundering and looks at published guidance.

KEY POINTS

- Why is money laundering so important to accountants?

- The application of the rules and examples of money laundering activities.

- Avoiding committing a money laundering offence

- The ‘Flag it up’ campaign and signs of money laundering.

- Risk assessment, potential tax fraud and deciding whether to report.

A dirty business

As the government relaunches its ‘Flag it up’ campaign against money laundering activity, Alex Byrne considers the important role played by accountants and tax advisers in combating the practice.

The Consultative Committee of Accountancy Bodies (CCAB) is the umbrella group of various chartered accountancy bodies: the ICAEW, ACCA, CIPFA, ICAS and Chartered Accountants Ireland. In March 2018, it published a new document, Anti-Money Laundering Guidance for the Accountancy Sector. My initial reaction was surely we did not really need a 73-page document that is not legislation and does not spell out the things to look for. Most accountants seek practical guidance on anti-money laundering, especially something they can pass on to staff to strike a balance between, at one extreme, failing to carry out the requisite procedures and, at the other, swamping the firm’s money laundering reporting officer (MLRO). However, on rereading, the guidance improves with familiarity.

Familiarity, not contempt

The anti-money laundering (AML) guidance has legal status, so accountants remaining unfamiliar with it or not applying its provisions do so at their peril. The regulations apply, with some exceptions, ‘to the persons (“relevant persons”) acting in the course of business carried on by them in the UK’. This includes (reg 8(2)(c)) auditors, insolvency practitioners, external accountants and tax advisers and (reg 8(2)(e)) trust or company service providers and company services in the UK, other than under a contract of employment.

The CCAB guidance confirms: ‘There is no definition given for the term accountancy services, however for the purposes of this guidance it includes any service which involves the recording, review, analysis, calculation or reporting of financial information, and which is provided under arrangements other than a contract of employment.’ So the regulations apply to businesses rather than their employees, although the latter will have responsibilities to ensure that the business is compliant.

The guidance also applies to bookkeepers, although it is suspected that many of these use their clients’ HMRC log-in details and are not registered with HMRC for AML purposes. But let’s begin with the basics to clarify money laundering and the measures that need to be taken to counter it – junior staff and some managers may have misconceptions.

What is money laundering?

In essence, money laundering is dealing with, or assisting someone else to deal with, the proceeds of crime; in other words, wealth of any sort – money, investments, land and buildings, cars and so on (Proceeds of Crime Act (POCA) 2002, s 327 to s 329).

Crime is defined as an action or omission that constitutes an unlawful act – an offence – and is punishable by law; for example, drug trafficking.

The ‘laundering’ is the legitimising of ‘dirty’ or illegal money obtained from crime, which cannot be deposited directly into a bank or other financial institution without raising questions. Consequently, criminals want to create financial records that give the money an apparent legitimate source. This might be by passing it through one or more legitimate businesses or using innocent individuals to deposit it in their bank accounts. By making the money appear to be from a legal source it is cleaned, hence the ‘laundering’ terminology. Anyone assisting with this even if not involved directly is also guilty of money laundering.

Large-scale criminal groups may use complex money laundering techniques to avoid detection, but there are other, more popular methods.

- Bulk cash smuggling. Cash is smuggled into another country and deposited in offshore banks or other financial institutions that ask few questions.

- Structuring. Also referred to as ‘smurfing’, cash is broken down into smaller amounts and used to purchase money orders or other instruments to avoid detection or suspicion.

- Trade-based laundering. This is similar to embezzlement in that invoices are altered to show a higher or lower amount to disguise the movement of money. For example, a car dealer may show a sale for £30,000, whereas the true receipt was £27,500. However, they bank £2,500 of criminal money at the same time, which is then drawn out and passed to the criminal less the dealer’s tax and share. The £2,500 has been legitimised and the net amount can be spent without questions being asked.

- Shell companies and trusts. These may be used to disguise the true ownership of a large sum of money.

- Bank capture. A bank is controlled by money launderers or criminals, who move funds through it without fear of investigation.

- Property laundering. This occurs when property is bought or developed with money obtained illegally, before being sold. Again, this legitimises the criminal funds and the proceeds can be spent without problem.

- Casino laundering. An individual buys casino chips with illegal money, gambles for a while, then cashes out the remaining chips with a cheque or bank transfer and claims this as winnings. However, casinos have been forced to tighten their AML procedures so this may now be more difficult.

- Money mule. Money is passed through an innocent individual’s bank account for which they are paid a commission. People are approached with different stories as to why this is necessary. Students in particular are susceptible. According to Cifas, the UK’s fraud prevention service, there were 8,652 cases of 18- to 24-year-olds having bank accounts used by criminals between January and September 2017.

- Cash-intensive business. A business that deals legitimately with large amounts of cash uses its bank accounts to deposit money obtained from everyday business proceeds and illegal money. The business declares the whole amount as legitimate. Commonly, such businesses provide services rather than goods and with low direct costs. Examples are strip clubs, nail bars, car washes and the like, but takeaways, night clubs and bars, convenience stores and restaurants may also be used.

Recent estimates suggest that between £36bn and £90bn is laundered through the UK economy each year. The amount that cannot be explained is seized.

Money laundering can be widespread and low key. For example, if a plumber pays a pub for drink with cash from an undeclared job, it is money laundering. The plumber is introducing dirty money into the legitimate money system. Of course, the pub may not be declaring all its takings, but that will not affect the plumber; they have obtained goods or services for the undeclared cash with no questions asked.

Omissions and accountancy service providers

Just knowing about money laundering imposes a legal duty to report it and, with some exceptions, a failure to report is a criminal offence. There is no de minimis threshold value for reporting.

Since accountants and tax advisers practise in the financial (‘regulated’) sector, they are subject to special regulations because they deal with the very financial transactions criminals want to legitimise. Accountants see bank accounts and know about clients’ earnings and expenditure. If a client has bank transactions that do not make sense or a more expensive house or car than would be expected from their business results or drawings, the practice has a duty to consider reporting this discrepancy to ‘a constable, a customs officer or a nominated officer’ (POCA 2002, s 338) unless there is an explanation with evidence.

Advisers must be aware of the importance of the anti-money laundering provisions because a failure to report is punishable by up to 14 years’ imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine. Further, civil penalties or criminal sanctions may be imposed on the business and any individuals in the business deemed responsible for failures.

In 2016, 1,435 people were convicted of money laundering in England and Wales. In R v Duff, the Court of Appeal upheld a six-month custodial sentence against a solicitor who had failed to report the receipt of £70,000 from a client to invest in a business when the client was later charged with drugs offences.

Avoiding committing an offence

Under paragraph 2.2.2 of the CCAB guidance, no offence is committed if:

- the persons involved did not know or suspect that they were dealing with the proceeds of crime; or

- a report of the suspicious activity is made promptly to an MLRO – in other words, an ‘internal’ suspicious activity report (SAR) is made within the accountancy practice; or

- a report of the suspicious activity is made promptly to the National Crime Agency (NCA) and before the offence takes place so that consent to proceed (referred to as a defence against money laundering by the NCA) is obtained in advance (POCA 2002, s 338, ‘Authorised disclosures’).

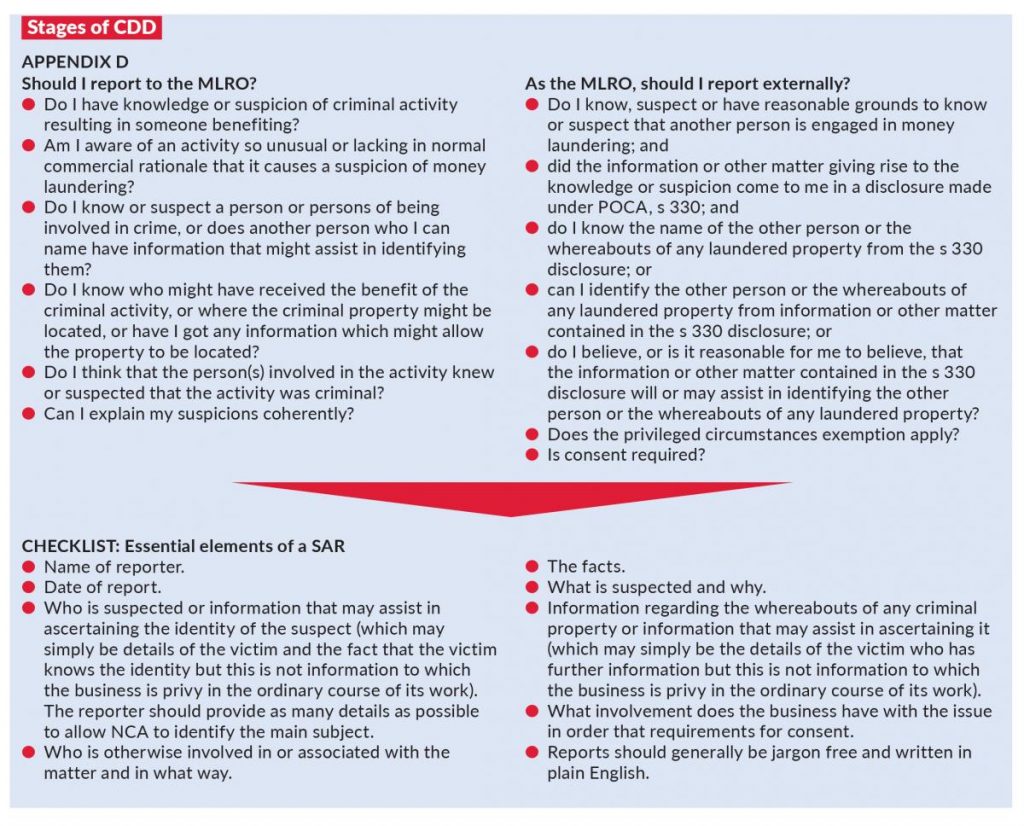

These are the exceptions most likely to apply, but the guidance does give others. To protect themselves, it is important for accountancy practices to train their staff to avoid unnecessary referrals while still complying with money laundering regulations. Section 5 of the CCAB guidance includes a table, Stages of CDD on customer due diligence.

Flag it up

The aim of the government’s recently relaunched ‘Flag It Up’ campaign (flagitup.campaign.gov.uk [2]) is to raise awareness of the warning signs of money laundering, promote best practice in due diligence and encourage the high-quality reporting of suspicious activity. It suggests advisers should be aware of several ‘red flags’.

- Clients – are they overly secretive or evasive? Do they refuse to provide all the necessary information and documents? Are there inconsistencies in what they say?

- Funds – is the amount and source of funds unusual? Is the client using multiple bank accounts or foreign accounts without good reason? Are the funds received from or sent to high-risk countries?

- Transactions – are there discrepancies in client transactions? Is the client involved in transactions that do not correspond to their normal professional or business activities? Are the transactions unusual because of their size, nature, frequency or manner of execution?

The Flag It Up website includes some short videos. Generally, however, published material fails to identify warning signs. It seems no one wants to be responsible for setting out detailed guidelines that may be too narrow in case accountants and staff work solely with these, do not recognise other issues and inadvertently allow money laundering. As a result, firms often struggle to carry out their anti-money laundering duties with some not doing it very well and failing because only the most extreme cases are referred. Many employees are simply unclear on what they should be looking for.

Staff who do not understand their responsibilities may feel that referring everything could be their ‘get out of jail free card’. If the number of submissions to the firm’s MLRO is a problem, or if managers feel staff are spending too long considering whether money has been laundered, it would be in the interests of the practice to increase training and focus on the problem areas. Staff should be made aware of the full contents of the guidance, but firms may wish to summarise its contents for admin teams.

Risk-based approach

The risk-based approach is twofold.

First, what I would call non-tax money laundering involving crime and terrorism which we should all be keen to identify and report to protect a civilised society and way of life.

Second, tax fraud. The CCAB guidance includes some examples of the former, although they may have tax implications.

The first example relates to shoplifting. The practice acts for a retail client and is aware of some instances of shoplifting. Should a report be made?

- Report – if the identity of the shoplifter, or the location of the shoplifted goods, is known or suspected, or if information is held that may assist in the identification of the shoplifter or the goods.

- Do not report – if none of the information above is held. No further work is required to find out this information.

Note that reporting does not force practitioners to be detectives or to gather more information than is normal in the course of their work. Following a client to obtain further information for a money laundering report is not required and could cause trouble. Everything that is required for a report should be available from the practitioner’s desk or meetings.

At paragraph 6.1.26, the guidance makes it clear that no attempt should be made to investigate matters unless to do so is within the scope of the professional work commissioned. It is important to avoid accusing or suggesting that someone is guilty of an offence.

The second example concerns overpaid invoices. Some customers of a client have overpaid their invoices. The client retains overpayments without attempting to contact the overpaying party. Do you report?

- Report – if it is known or suspected that the client intends to dishonestly retain the overpayments. Reasons for such a belief may include the client omitting overpayments from statements of account.

- Do not report – if the client has sought and is following legal advice on the overpayments.

The third example relates to illegal dividends. A client has paid a dividend based on draft accounts. Subsequent adjustments reduce distributable reserves to the extent that the dividend is now illegal.

- Report – if there is suspicion of fraud; in other words, if the client did this deliberately knowing there were insufficient reserves.

- Do not report – if there is no such suspicion. The payment of an illegal dividend is not a criminal offence under the Companies Act 2006.

The guidance also includes examples of invoices raised by overseas consultants lacking commercial rationale that might be bribes, and concerted price rises that could be price fixing. The guide reminds us that money laundering offences include conduct occurring overseas that would be an offence if they had happened in the UK.

The Financial Action Task Force points out that some countries are deemed to have a higher risk of money laundering activity: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK); Ethiopia; Iran; Pakistan; Serbia; Sri Lanka; Syria; Trinidad and Tobago; Tunisia; and Yemen.

Potential tax fraud

I am not associating the AML guidance with the instances of money laundering that I am giving below, nor do these examples encompass everything that practitioners need to look for. They are drawn from my experience to provide a firm base for a small practice to work from when compiling its AML procedures, especially if it is not subject to supervision by one of the main accountancy bodies.

For day-to-day accountancy and tax work, there are many common issues that could be considered for potential tax fraud.

- Unusual or large transactions, large bank withdrawals for which the destination is not known, especially to a financial institution in a country known to be a low tax or secrecy haven.

- Complex, unusual patterns of transactions or uncharacteristic transactions.

- A sudden increase or reduction in business turnover.

- Unexplained capital introduced, including many relatively small deposits. These may indicate a larger sum has been split to enable smaller, less suspicious deposits to be made. A deposit from another bank account raises the question of where the money in that account came from.

- Income or means that appear insufficient for the apparent lifestyle (including the settlement of credit card accounts) or savings

- Company losses and no other apparent income.

- Capital assets, such as the purchase of cars or houses for which there is no explanation of the funding.

- Poor or incomplete records that might indicate omissions or false records, such as invoices.

- Cash businesses for which there are:

- sizeable deficits or surpluses on cash account – possibly a sign of loose cash control;

- more cash deposits than would be expected from a business of that size;

- large cash transactions inconsistent with the trade (the sign of a cash hoard or cash not being declared, which could be encouraging others to avoid tax); or

- no cash sales when some would be expected or cash sales when they would not be expected.

- No face-to-face contact or a remote client. The lack of a face-to-face meeting with a client may indicate a higher risk of fraud and steps should be taken to minimise the risk.

Staff should be aware of these warning signs so they can be flagged-up to the firm’s MLRO.

Planning point

Just knowing about money laundering imposes a legal duty to report it and, with some exceptions, a failure to report is a criminal offence. There is no de minimis threshold value for reporting.